I'm preoccupied with autumn. It's not so much the orange leaves, or blackberries between thorns; I'm not a fan of 'pumpkin spice'. No, for me, autumn is the inevitable descent into winter's chaos.

We don't get much snow on Islay—a little, rarely, not enough to block the door—but the storms: the ones that steal your boat and rip branches from the trees; the nights of flying trampolines, when the lights go dead, and we have to read with candles. I shouldn't like them, I know, but I watch the Atlantic forecast, in anticipation, waiting for one to hit.

Scotland and Iceland, they're woven together: Old Norse place names scatter the west coast; a certain, cynical humour; a propensity, on occasion, to drink oneself under the table... The lands, themselves, each other warped: Scotland's volcanoes are long dead, its glaciers melted to bog, Iceland's missing trees and Scotland's missing steam vents, but these skerries, sker, they crumble off both coasts.

The thrift that clings between the rocks is in the Highlands too; the birds are shared: fulmur, skua... I'll stop at naming two; a spongy carpet's fragile moss; and, not least, those wandering sheep that cause more trouble than they're worth, to most, but not a few...

Watching, back tracking, the Atlantic weather forecast, a seething mass of purple-blue—twenty meters per second, thirty meters per second...—engulfs the space between these nations, obliterating the Faroe Islands and Shetland. Spending autumn, early winter, in Landmannalaugar, I'd speak to my family in Islay, and hear a story of the same squall.

British people, all, like to talk about the weather, but Icelanders and Scots have more to discuss: roads close, ferries stop, and people get trapped in their houses. It's worse for those who go out regardless; some work never stops.

So autumn, yes, when the darkness begins to colonise the day. Mid-summer steals the waking hours from northerly lands, and the debt must be paid by December. The sun's slow rise and fall basks the sea in orange glow—on calm days, that is, otherwise we see nothing. In Iceland, I spent those hours, the quiet ones, preparing for wind and snow: weigh the things down, gather them together, fix what you can, when you can, and close the windows (please). One day, we knew, the sun wouldn't rise above the mountain.

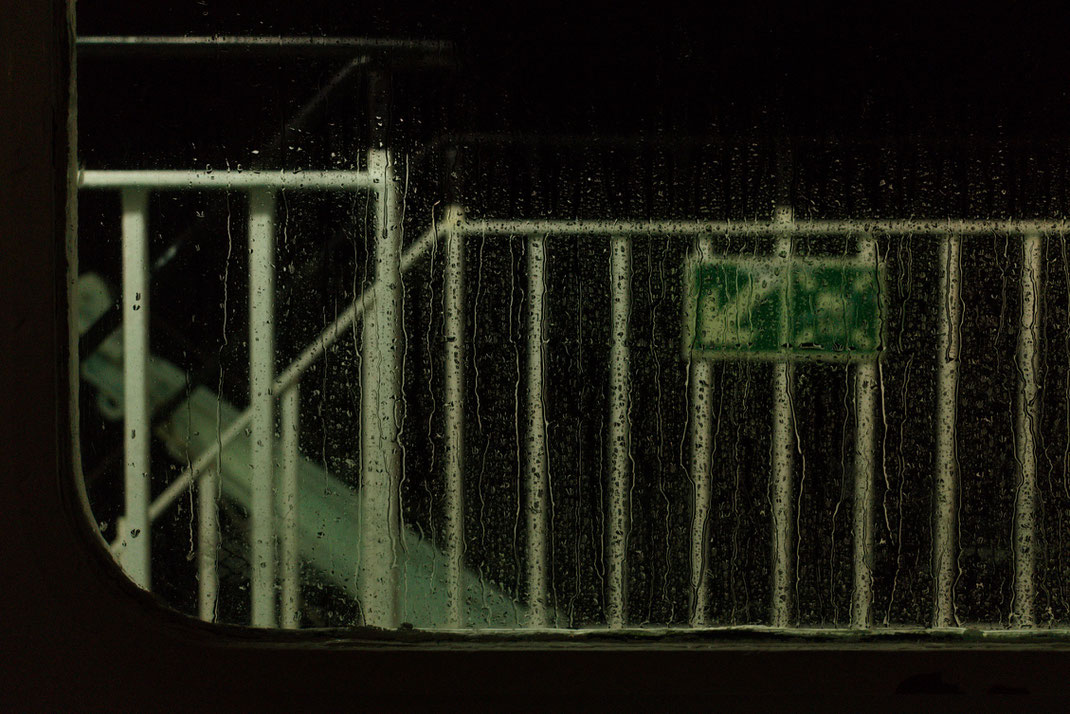

Landmannalaugar, autumn/winter 2019

Here, Islay, I don't have property to manage (we live in a sublet council house). If I'm outside, which I try to be, I'm obsessed with using these hours: to do everything, see everything, before it's too late and I can't. I glide along on my new [to me] bike, childish fingers with ragged nails clinging onto the rubber of my handlebars—it's not perished and ripped like the ones I'm used to, but the brakes still screech when it's wet. The wind whistles through my helmet, whipping my hair across my face no matter how tightly I tie it. Hail stings my skin. Often, unceremoniously, I dump my bike beside the road. To see the sea from a distance, even just a few meters, is usually not enough—I want to hear the water crash through rocks, to risk my feet getting wet.

The turquoise water on still days is inviting, though less so when I try, but I'm waiting for the terror of surging surf—those waves that smashed a thousand ships—centuries of tragedy in Hebridean seas. Of course, even in a reckless mood, I've never wanted that.

I'm thankful for Scotland's guiding lights, seven around Islay alone. How many people fancy themselves as a lighthouse keeper? Too many, it's cliché, but I've thought of it often, in Iceland too—a mountain hut warden, in winter, when nobody came, and we were alone with the mice. Tasks made harder by weather and light; electricity and water short, and even less food by the end. We were playing at it, that time, as we sheltered in our wooden hut—geothermally heated—and I couldn't sleep in fear that one of those rocks, battering our windows, would finally find its way through, or, maybe, the brown torrent, Jökulgilskvísl, would continue to rise and sweep away the house. That delightful boredom, forced inside, and listening to the racket, rok og rigning, intent on destroying the house.

When we survived, as we knew we would, the invincible feeling was hard to shake—to climb down from—and you (I) began to want to test it again.

The next autumn, winter, I was locked down in an English city. The city's dangers were human, but I ran through the dark, headphones blaring, along the banks of the river: daring a problem, that never arose, to wake me from my coma. I cycled then too, through necessity mostly, home from work at midnight: zipping silently through streets and parks, splattering my back with mud and grit, and squinting through the rain.

It wasn't the same, but it helped.

Islay is somewhere in between. I'm not a lighthouse keeper and, anyway, I'm too afraid of the sea. The descent to chaos won't be absolute: my house will never be buried in snow; the sun will rise above the hill, but I know there'll be a taste of this madness. I can climb Beinn Bheigeir in the battering rain; or run, t-shirt and shorts, through the hail. The day will come when to ride a bike won't be possible, for me, with a side wind and risk of falling trees. I'll complain when it happens, like we all do, but I'll know, right then, I'm awake.